Fair World Project recently participated in writing an International Guide to Fair Trade Labels. The main purpose was to evaluate fair trade labels, making both generalities about them collectively and looking at each in detail. One aspect of this evaluation was to look at how fair trade labels differ from other eco-social labels. This was particularly important for FWP since it is a question that comes up a lot.

There is a great deal of confusion about eco-social labels. One reason for this is because labels like Rainforest Alliance and UTZ and other eco-social labels certify the same commodities—tea, coffee, chocolate, sugar, etc. But they are sometimes more intentionally advertised as fair trade, for example a product that carries a Rainforest Alliance label and a description of fair trade.

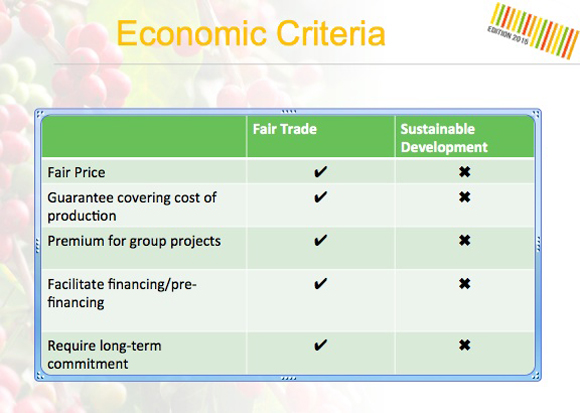

But they are not the same. One of the biggest points of differentiation is in the economic criteria. None of the eco-social labels we evaluated in the guide guaranteed a fair price or even guaranteed covering the cost of production, none provided a premium for group community development projects, none offered or facilitated pre-financing, and none required a long-term commitment. All of the fair trade programs (with the exception of Forest Garden) covered all of these criteria. If price is addressed by the eco-social programs at all, it is only to assume that an economic boost for farmers will be the natural outcome of increased yield or quality of the demand for certified products. Directly addressing the economic transaction by guaranteeing a better price and empowering producers to better compete in the marketplace is a hallmark of fair trade.

While the eco-social labels are strong on many of the environmental criteria like protecting biodiversity, only one eco-social label, 4C, completely bans GMOs. Rainforest Alliance allows farmers to grow GMOs as long as they are kept separate from the certified non-GMO products.

The most important conclusion from the labeling guide is that, “Sustainable development labels do not seek to change the practices of companies that buy certified products…In contrast, in fair trade the relationship with business partners is expected to change.”

We have written before about the shortcomings of fair trade certifications and our own certifier analysis tool points to differences among labels. The key here is that fair trade certification is embedded in a movement that is seeking to change trading relationships. Although certification alone cannot bring about the changes we seek, it is significant that other eco-social labels do not even share this goal or vision.

To learn more about the individual eco-social labels evaluated in the guide and how they differ from fair trade, see chapter 3 of the guide as well as this presentation given at the Fair Trade International Symposium in Milan in May 2015.