Follow these simple techniques to learn how to make biscotti that’s crispy and delicious every time.

It’s not difficult to master the techniques to make perfect biscotti–mixing and shaping the dough, slicing the baked logs, toasting nuts, melting chocolate, and so on. Read through this section to familiarize yourself with the techniques used to make biscotti. As with any cooking or baking process, the more you do it, the more accomplished you become.

Prepping Nuts

Many biscotti recipes call for toasting nuts or removing their skins, or both. Follow these simple instructions to remove the skins from almonds, hazelnuts, and pistachios.

Almonds

Place raw, skin-on almonds in a heat-proof bowl and pour boiling water over them. Let sit about 1 minute to loosen the skins. Drain and rinse, and use your fingers to pop the almonds out of their skins.

Hazelnuts

Heat the oven to 350 degrees Fahrenheit. Spread the shelled nuts on a rimmed baking sheet and bake for 10 minutes, or until the skins have begun to crackle. Wrap the hot hazelnuts in a clean kitchen towel and let stand about 1 minute. Roll the nuts back and forth in the towel to loosen and rub off the skins. Not all the skins will come off, which is fine.

Pistachios

Place the nuts in a heat-proof bowl and pour enough boiling water over them to cover. Let sit for 2 minutes and then drain. You can either slip the skins off with your fingers or wrap the nuts in a clean kitchen towel and roll them back and forth to remove the skins. I find the towel method removes some of the skins but not all, so I use my fingers.

Toasting Nuts

Heat the oven to 350 degrees Fahrenheit. Spread the shelled nuts on a rimmed baking sheet and bake for 7 to 10 minutes, until they are fragrant.

Toasting Coconut

Heat the oven to 325 degrees Fahrenheit. Spread the flakes on a rimmed baking sheet and bake, stirring once or twice, for 3 to 5 minutes, or until the flakes are lightly browned. Keep a close watch, as coconut can quickly go from browned to burned.

Toasting Fennel Seeds

Spread the seeds in a dry heavy skillet and set over medium-high heat. Gently shake the skillet or stir the spices with a heat-proof spatula to move them around as the skillet heats. Cook for 3 to 5 minutes, just until the seeds have turned a shade darker and are fragrant.

Measuring Flour

The most accurate way to measure flour is by weight in grams. Use a digital scale with a metric setting if you have one. If you don’t and are measuring by the cup, lightly spoon the flour into a measuring cup until it is overflowing, and then sweep across the top with the flat edge of a knife or metal spatula to level. Do this over a piece of wax paper to catch the excess flour.

Melting Chocolate

To melt bittersweet, semisweet, or milk chocolate, chop coarsely and put the pieces in the top of a double boiler set over (but not touching) barely simmering water. Or put the pieces in a heat-proof bowl and set the bowl over (but not touching) a pan of barely simmering water. Heat, stirring gently, until the chocolate is melted and smooth. To melt in the microwave, put the pieces of chocolate in a microwave-proof bowl and microwave at 50 percent power in 30-second intervals until melted and smooth. Stir after each interval.

Mixing Biscotti Dough

The traditional method is the same one used to make fresh pasta. That is, you mound your dry ingredients on a countertop, make a well in the center, add in your eggs and other “wet” ingredients, and gradually incorporate the wet into the dry until a dough is formed. However, modern convenience has given us the stand mixer, which I find works just as well. I fit my stand mixer with the flat paddle attachment, which I prefer to the whisk attachment because it mixes the ingredients without incorporating too much air. It also does a good job of breaking up nuts, but not too finely. You can use a food processor, again starting with dry ingredients and adding in the wet ones. However, I find the blade tends to chop the nuts too finely.

Chilling the Dough

This is optional, done mostly for convenience. You can chill it for as little as an hour or as long as overnight. Because biscotti dough is often soft and sticky, refrigerating it until firm makes it easier to handle and shape into logs. Generally, though, I like to shape the dough right after mixing it and get on with the baking.

Shaping the Dough

The soft, tacky dough can be tricky to handle, as it has a tendency to cake on your fingers. It can be difficult to roll out into a log shape and cumbersome to transfer to the oiled baking sheet. After trying a number of different methods, I settled on this one, which is not especially elegant but is easy and works beautifully. Place the dough on a lightly floured countertop and divide it according to the recipe instructions. Lightly moisten your hands, either with a tiny bit of water or with vegetable oil. Shape a portion of dough into a rough oval and, with moistened hands, transfer it to the prepared baking sheet. Then use your hands and fingers to gently stretch and pat the dough into a log shape.

The size of the log will depend on the recipe. Some recipes call for wide logs, to yield bigger biscotti. Some recipes call for dividing the dough into three or four portions to yield smaller logs to make smaller biscotti. Of course, you can make the biscotti any size you prefer.

Using Egg Wash

Most traditional recipes for classic cantucci call for brushing the log of dough with beaten egg before baking. This creates a glossy surface. I have kept this step in a few of my more traditional recipes. But in most of the recipes I omitted it because I happen to like the more rustic nonglossy look.

Baking the Logs

All of the recipes call for baking the logs of dough at 350 degrees Fahrenheit. Once sliced, the biscotti are returned to the oven at a lower heat–300 to 325 degrees Fahrenheit–for a second baking, the purpose of which is to dry them out without browning them too much. The biscotti made without butter or oil become crunchy during this second baking, while those that contain a little fat tend to be crispy and a little more delicate in texture. Keep in mind that the biscotti will get crunchier as they cool.

In general, it takes 25 minutes for an uncut log to bake. You can tell when it’s done by pressing lightly on the top–it should spring back and there should be cracks on the surface. After slicing, the second baking can take anywhere from 8 to 20 minutes per side, depending on whether there is fat in the dough, how thickly you slice the log, and how hot the oven is.

Slicing the Logs

After the first baking, the logs are sliced on the diagonal to make that classic angled biscotti shape. The more acute the angle of your knife, the longer your slices will be. And (obviously) the thicker the slice, the fatter your biscotti will be. I sliced the biscotti in these recipes according to how I wanted the finished cookies to look and how big or small I wanted them to be. For example, I sliced the Cappuccino Dunkers on an acute angle to create long cookies perfect for dunking. But for the Sun-Dried Tomato and Fennel biscotti, I made thin logs, which I then cut into fat slices to make two-bite savory cookies that are perfect appetizer size.

For years, I used a serrated bread knife to gently saw the baked logs into slices. Although this works fairly well, pieces of nuts can snag on the knife’s teeth, which causes the occasional cookie to crumble or break. Still, it works better than a chef’s knife, which has a tendency to compress and flatten the slices. But I recently found a better way. I was at a farmers’ market in Glen Arbor, Michigan, where I met a woman selling homemade biscotti. We got to talking and she mentioned she uses a Santoku knife–a Japanese knife with a flat-edge blade. This, I found, works beautifully. No sawing required. Just press down and cut as though you were slicing an onion. The Santoku slices through the log without compressing it. So a tip of the hat to that Michigan baker who shared her secret. If you don’t have a Santoku, use a serrated bread knife.

Icing Biscotti

A number of recipes call for dipping biscotti in melted chocolate or for drizzling melted chocolate or a sugar-based icing over them. Follow the instructions for melting chocolate. To minimize mess, I line a rimmed baking sheet with wax paper or parchment paper and set a cooling rack over it. You can either lay your biscotti on their sides or stand them upright. To drizzle, dip a fork or the tip of a whisk into the icing (or melted chocolate) and wave it back and forth over the cookies. Chill the biscotti briefly in the refrigerator to set the icing.

Storing Biscotti

Most biscotti last at least a week. Those made without butter or oil last longer, at least two weeks. To keep them crisp, store biscotti in metal containers with tight-fitting lids at room temperature. I don’t recommend refrigerating or freezing biscotti, as they tend to lose their crunch when defrosted.

More from Ciao Biscotti:

• Fig Biscotti Recipe

• Savory Biscotti Recipe with Gorgonzola and Walnuts

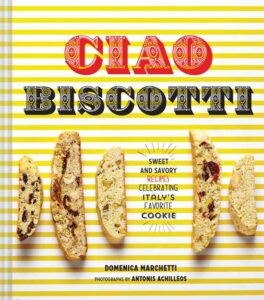

Reprinted with permission from Ciao Biscotti: Sweet and Savory Recipes for Celebrating Italy’s Favorite Cookie by Domenica Marchetti and published by Chronicle Books, 2015.